Introduction

VCNZ has had CPD requirements for veterinarians since 2011. Over the last year, we have reviewed the current requirements to make sure that they are still fit for purpose, are easy for veterinarians to follow and are in line with current evidence on professional development and learning. In tandem with this project, we have also researched whether a formal support programme would benefit new graduates in their transition to professional practice.

This document sets out our findings and what changes we’re proposing to make as a result. The aim is for veterinarians (and others) to understand the changes we are thinking about so that you can tell us what you think. No final decisions have been made yet and we welcome all comments on these proposals.

Why we are proposing changes

The CPD requirements were introduced in 2011 and we now have new thinking and evidence to help us improve the system. We want a CPD system that:

- Works to ensure veterinarians maintain up to date knowledge and skills

- Promotes self-reflection, continued learning and performance improvement

- Enhances public confidence in the veterinary profession.

We also want the system to have the least possible impact on veterinarians in terms of time, administration and money and it needs to be as effective and easy to use as possible.

The consultation process

We want to hear from veterinarians and others about what you think of these proposals. Once we have feedback, we will consider whether any changes are needed to the proposals and then make a final decision on whether to go ahead. If we decide that major changes to what is proposed are needed based on the feedback we receive, we will seek further comments on the updated proposals before making a final decision.

The current situation

All practising veterinarians are required to undertake CPD. CPD is divided into 3 categories, Continuing Veterinary Education (CVE), Collegial Learning Activities (CLA) and Self-Directed Learning (SDL). Points are earned by undertaking set numbers of hours of each activity. Veterinarians must gain at least 60 points in a rolling 3-year period with at least 15 points each in CVE and CLA.

Veterinarians are asked to declare their CPD points each year when they renew their annual practising certificate and we work with veterinarians who have not earned enough points to help them improve. We carry out audits each year of a small percentage of the profession to compare the declared points against their records.

More information about current requirements can be found on our CPD page.

Our research

To research the current situation, we:

- Reviewed the literature available on CPD and continuing competence in veterinary and medical professionals.

- Surveyed the NZ veterinary profession on CPD and the current scheme.

- Surveyed new registrants (those registered with VCNZ in the previous 5 years) on their experiences and preferred options for support from VCNZ.

- Surveyed supervisors, employers and colleagues of new registrants on the same.

We'd like to thanks everyone who took part in our surveys. Your input made this work possible and will help shape CPD.

Citations and access

All 4 pieces of research have been written-up and either submitted or already accepted for publication in peer-reviewed journals.

- Gates MC, McLachlan I, Butler S, Weston JF (2020) Experiences of new veterinary graduates in their first employment position and preferences for new graduate support programmes. Accepted in New Zealand Veterinary Journal (Available online)

- Gates MC, McLachlan I, Butler S, Weston JF (2020) Building veterinarians beyond veterinary school: challenges and opportunities in continuing professional development. Accepted in Journal of Veterinary Medical Education (In press)

- Gates MC, McLachlan I, Butler S, Weston JF (2020) Practices and preferences of New Zealand clinical veterinarians for continuing professional development. Under Review in New Zealand Veterinary Journal

- Gates MC, McLachlan I, Butler S, Weston JF (2020) Opinions and experiences of employers and colleagues with new graduate veterinarians during their first year in clinical practice. Under Review in New Zealand Veterinary Journal

NZVA members can access the NZ Veterinary Journal through SciQuest. Those who want to read the full articles and are unable to do so easily, can contact us for access.

The detailed results are available in those articles. The key results and the conclusions we have drawn from them are summarised below.

Our findings

Survey of veterinarians on CPD

We invited all practising veterinarians to tell us about their experiences with, and views on, CPD. 222 veterinarians provided a complete survey response. We found that most respondents were completing CPD and it was having an effect on their practice. However, most found categorising and recording CPD to be a burden and there was strong support for simplification.

See our key findings

The most significant findings were:

- Most respondents were satisfied with the amount of CPD they completed.

- The most popular formats for CPD were those involving collegial interaction (including conferences and skills training workshops).

- Choice of CPD was most commonly influenced by interest in the topics and a desire to become more competent.

- Difficulties fitting CPD around work and family commitments were the main barriers to undertaking CPD.

- Nearly 75% of respondents could cite at least one occasion in the last 12 months where participating in CPD caused them to change how they worked.

- Recording CPD under the current system appears to pose an administrative burden for many.

- There was some concern about the reliability of using CPD audits to evaluate competence.

- There was strong support for simplifying the CPD categories, developing a tool to record and share CPD activities in real-time, and developing skills checklists.

Literature review on CPD

We also conducted a review of current literature focusing on:

- Defining what it means to be professionally competent across different career stages

- Delivering CPD that is effective in promoting evidence-based medicine and behavioural change in practice

- Developing reliable and sustainable systems to assess CPD and continued professional competence.

The most significant theme from international literature was the importance of interacting with colleagues and the value of external feedback. This helps evaluate strengths and weaknesses and develops stronger support networks for managing the stressors of veterinary practice.

Read more about our findings

Other notable findings included:

- Many studies have shown that simply participating in CPD is often not enough to motivate behavioural change or improve clinical outcomes.

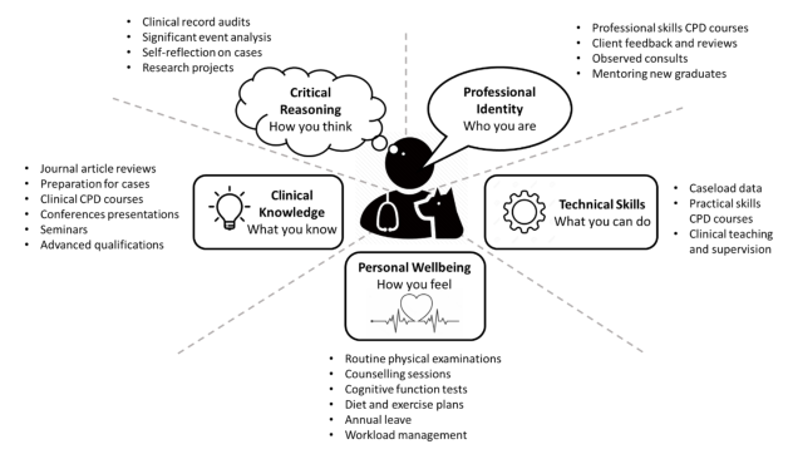

- There is increasing recognition that non-technical competencies (such as critical reasoning, communication skills, business management and personal wellbeing) are important factors in practising as a competent veterinarian.

- Veterinary competence can be defined to include the following 5 areas:

- Early career veterinarians have reported that they appreciate having skills guides that identify core skills for clinical practice (such as that produced by the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons in the United Kingdom).

- A number of overseas veterinary regulators have implemented or are considering new graduate support programmes. These tend to focus on building clinical knowledge and technical skills but employers and new graduates have primarily identified non-technical skills such as client communication and business management as key areas for new graduate development.

- Most new graduates appear to rely heavily on their colleagues for support in developing their skills and they prefer informal learning opportunities over formal courses and structured checklists.

- For mid-career veterinarians, the two main continuing competency issues faced are burnout associated with factors like stress, compassion fatigue, workload and boredom, and maintaining fitness to practise during and following career breaks or when transitioning to a different area of practice.

- Multiple studies have shown that burnout is a common problem and that it can lead to negative outcomes such as clinical errors, substance misuse and poor mental health. This suggests a need to incorporate wellbeing into CPD to provide veterinarians with the necessary skills to tackle the problems that give rise to stress.

- Incorporating soft skills training into CPD programmes has been shown to have benefits on reducing stress.

- Late career veterinarians face the possibility of cognitive and physical ability declining with age, which they may be unaware of, and there is evidence to show that this happens. However, there is also evidence of many older medical practitioners with similar levels of performance to their younger peers.

- Participants in a study in the medical field reported frustration at the lack of institutional support that would allow them to continue making a contribution to their field even if they were no longer engaged in hands-on clinical practice and this may have influenced decisions to postpone retirement.

- CPD topics for veterinarians tends to be self-selected. This is potentially concerning due to the Dunning-Kruger effect, which is a well-documented cognitive bias where individuals with the least knowledge or competence in an area are the most likely to overrate themselves in that area. This suggests individuals may not be able to accurately self-identify the areas where they need the most improvement.

- While frameworks may be useful to help veterinarians become aware of areas of knowledge and skills they need to maintain, highly prescriptive topic requirements carry the danger of practitioners seeing CPD as a regulatory box-ticking exercise rather than a chance to improve skills.

- CPD appears to be most effective when individuals are directly involved in creating plans that are tailored to their specific needs.

- Evaluating the effectiveness of different types of CPD using literature is difficult because different studies have used different criteria. However, there is evidence from the medical field suggesting that traditional didactic formats (such as conferences, workshops and rounds) do not have a significant impact on clinical performance unless the sessions were more interactive in nature.

- There is no strong evidence that online CPD is any more or less effective than face-to-face formats but there are studies suggesting that e-learning portfolios can be a valuable tool for helping people keep track of their learning.

- There is evidence of challenges across all professions in translating new knowledge to behavioural change. The most commonly cited barriers to change are insufficient time, difficulty in identifying and accessing relevant journal articles, inability to understand research findings and lack of authority or ability to influence change in a practice.

- While there is no clear evidence favouring any particular format of CPD, some themes emerge from the literature including the importance of interactions with peers, the value of including some form of assessment or self-reflection at the end of a CPD activity and the benefit of encouraging practitioners to think about how their learning can improve their performance.

- There does not appear to be a strong correlation between the recorded completion of CPD activities and continued professional competence suggesting the need for new frameworks to identify those individuals who are not performing up to standard without placing unnecessary burdens on those who are.

- One of the key challenges in assessing continued professional competence is the lack of agreement within the veterinary profession around what constitutes appropriate levels of care.

Survey of new graduates

We invited all people who registered for the first time with VCNZ in the past 5 years to take part in a survey about the employment experiences and desires for a support programme. This identified that poor culture, lack of support and being put in situations they could not handle were issues for a significant proportion of respondents. New graduates indicated that they would prefer a support programme that put requirements for supervisors to have regular meetings with new graduates (or a non-compulsory version of this).

Read more about our findings

There were 162 responses. Key findings were:

- Approximately 45% of the new graduates surveyed had left their first place of employment with the most common reasons cited as toxic practice culture and lack of adequate support.

- Being put into situations they could not handle and having employers that did not regularly check on their wellbeing significantly increased the risk that a new registrant would leave their first place of employment.

- New registrants indicated that employers need to address the following issues:

- Providing regular feedback

- Creating a supportive practice culture

- Setting reasonable and realistic workload expectations

- Providing clinical and professional advice

- Developing tailored skills development plans.

- When asked about their experiences at their first place of employment, respondents tended to agree that their employers made sure there was another experienced veterinarian available to ask for advice.

- Respondents tended to disagree that employers checked on their wellbeing, met regularly with them to discuss their work and had a clear plan to develop their skills and experience.

- When talking about their current job, respondents generally agreed or strongly agreed that they enjoyed their work but disagreed or strongly disagreed that their remuneration was fair in relation to other professions.

- When asked about preferences for a new graduate support programme:

- Requirements for those employing new veterinarians to hold regular meetings between employee and supervisor or introducing a non-compulsory programme where new graduates could meet with experienced veterinarians were ranked as the most helpful.

- Compulsory and non-compulsory skills checklists were ranked as the least helpful.

- Just over half of respondents would support a compulsory programme involving regular meetings with an experienced veterinarian.

- Some comments indicated a need for support and training for those mentoring new graduates.

Some caution is needed in interpreting the results of this study since there is the potential for voluntary response bias, meaning that individuals with strong opinions about the subject were more likely to have responded to the voluntary survey. There is also the possibility that some respondents may have been reluctant to share details of their experiences with VCNZ (even anonymously).

Survey of employers, supervisors, mentors & colleagues

We also surveyed those who have employed, supervised, mentored or worked with new graduates. This group reported that regular supervision meetings discussing performance and wellbeing, compulsory sessions with an experienced veterinarian for career advice and non-compulsory skills checklists would be the most helpful interventions but there was not strong support for including these in a new graduate support programme run by VCNZ.

Read more about our findings

We received 83 responses. Some of the main results were:

- New graduates exceeded expectations in their ability to research cases and communicate with colleagues and clients.

- However, they were often below expectations in their time management and awareness of financial issues.

- Respondents spent, on average, 166.8 total hours supervising new graduates during their first year in practice (around 3 hours per week). Across the first year, the average was:

- 23.6 hours in the first month

- 18.5 hours per month during months 2 to 3

- 13.8 hours month during months 4 to 5

- 11.3 hours per month during months 6 to 8

- 10 hours per month during months 9 to 12.

- Respondents tended to agree with the statement that new graduates were provided with adequate support.

- For those answering questions about a new graduate who had left their first job, the most common reasons given for them leaving were relocation due to family commitments, lack of support or mentoring, routine workload too high, and afterhours workload too high.

- When asked about preferences for a new graduate support programme:

- Regular meetings between a supervisor and the new graduate to discuss performance and wellbeing, having compulsory sessions with an experienced veterinarian for career advice and non-compulsory skills checklists were ranked as the most helpful.

- Fewer than half of respondents supported including the above measures in a new graduate support programme.

- Requiring compulsory annual conversations with a counsellor and compulsory checklists for non-technical skills were ranked as the least helpful options.

- Concerns around seven themes emerged from free text comments:

- Insufficient preparation of students in veterinary school.

- The need for a transition phase (particularly for weaker performers), functioning like an internship.

- Employers lack adequate training and resources to supervise new graduates.

- There is poor return on investment for mentoring new graduates.

- Providing too much support may discourage independence.

- There is a generational change in the attitude and expectations of new graduates with a few respondents reporting new graduates had less work ethic, resilience and willingness to take on responsibility.

- Poor mental and physical wellbeing of new graduates as a result of bad experiences during their first year of practice.

Conclusions

Based on the research into CPD, we reached the following conclusions:

- We found no evidence that assigning or counting CPD points is effective in ensuring that veterinarians are developing professionally or maintaining professional competence. This appears to be an unnecessary complication for veterinarians and we do not believe it is necessary.

- Categorisation of CPD activities in the current system appears to be causing unnecessary confusion and complexity for veterinarians.

- Instead of collecting points and categorising activities, it would be more effective for veterinarians to:

- Prepare a CPD plan, focussing on their learning needs. This should include a component of rating their current knowledge and skills to identify areas to focus on.

- Review their plan and learning.

- Record outcomes (what the key learning was and some action points to take away from it) for each activity they take part in.

- Collegial input on planning and evaluation of CPD and performance has a high impact on continuing competence and should be strongly encouraged.

- The 5 areas identified in the literature review provide a good framework for ensuring a good breadth of continuing learning.

- A framework with key learning areas in each domain could be a useful tool to help veterinarians review their current practice and plan their CPD. Customisation would be needed for different areas of practice.

- There would be benefit in providing training for veterinarians on how to get the most from CPD and ensure continuing competence.

Based on the research into new graduate support, we reached the following conclusions:

- New graduates would benefit from preparing a plan at the start of their employment (or earlier) as a veterinarian, with the help of a mentor or supervisor, to identify their learning needs.

- The 5 domains of learning and skills framework described above would help with this planning process.

- Regular meetings with a mentor or supervisor to review progress against the plan and check on general wellbeing would be of major benefit to new graduates. There is no evidence about how often this should take place but common sense suggests that at least monthly for the first 3 months and bimonthly after that would be a good starting point.

- There should be flexibility around who can be a mentor or supervisor to allow for different situations. A mentor could be an employer or manager or it could be someone independent from the place of employment.

- Training should be available for mentors and some have suggested that it should be mandatory.

- There is an apparent disconnect between the level of support that new graduates perceive they have received and level of support that employers believe they have provided that needs to be addressed. These proposals should help, but this is a wider issue for discussion in the profession.

Proposed changes for experienced vets

Our aim is for veterinarians to do enough CPD to keep themselves up to date and competent. We are proposing to remove the current points-based system. Veterinarians will no longer be required to convert their hours of CPD to points nor to collect a certain number per year. Veterinarians will also not be required to divide their CPD into different categories. As discussed above, we found no evidence to support that an arbitrary amount of CPD per year is effective. We heard from veterinarians that the points system and categorising CPD poses an administrative burden and we do not consider that this is justified when looking at what we want to achieve from CPD.

Instead, we propose to require that veterinarians:

- Prepare a CPD plan

This would consist of identifying their current learning needs to help choose what CPD to undertake. We would expect veterinarians to plan to do CPD that covers all 5 areas of competence. We could produce guidance material summarising key knowledge and skills for different areas of practice to help with the planning process.

- Do CPD

We don’t intend to set a fixed amount of CPD that must be done (although we can provide some general guidance if needed) but we will expect veterinarians to take part in quality CPD that is relevant to their practice. Ideally, this should reflect what is in the CPD plan but there will also be scope to take advantage of learning opportunities that arise, even if they aren’t in an area identified in the CPD plan. We would expect veterinarians to ensure that their CPD activities cover all 5 areas of competence (bearing in mind one activity might cover multiple areas).

- Record CPD activities

For each CPD activity, record briefly what was done, key learning points and one or more action points (changes to put into practice) to take away from it.

- Review the CPD plan

Regularly (at least annually) review and update the CPD plan to make sure it is focussed on current learning needs.

We found that collegial input, the opportunity for feedback and reflection are more important than what format the CPD is delivered in. While the CPD categories were designed to encourage CPD that had these components, it appears to be causing confusion, does not encourage reflection and is not always good at encouraging good quality feedback.

The things that need to be recorded as part of step 3 above should help encourage a minimum level of reflection and veterinarians can choose to reflect in more depth if they choose.

We considered whether to require some form of collegial input into the planning and reviewing steps. While collegial input is of high value and strongly supported by the evidence as effective, we concluded that it would be better to encourage this for now rather than mandating it. We believe that the profession would be unlikely to respond well to such a requirement. Rather, we will strongly encourage peer input the planning and reviewing processes and emphasise the value that collegial interaction adds to CPD activities.

What resources will VCNZ provide?

We are planning to produce resources for veterinarians, including:

- Guidance material summarising key knowledge and skills for different areas of practice, structured around the 5 areas of competence

- Instructional information on the planning and review processes and how to get the most from them

- Information on how to identify effective and high quality CPD

- Information on how to record CPD activities, particularly around identifying action points

- Learning material (which could count as CPD) on how to get the most from CPD and undertake effective CPD activities.

We will also consider whether to create a system for veterinarians to record their CPD with VCNZ directly, if they wish. If we go ahead with this, we will work with NZVA to ensure that it is compatible with their system.

How will VCNZ tell whether a vet has complied?

We still plan to carry out compliance reviews (audits) each year. Instead of focussing on whether enough points have been earned in each category, these will focus on the quality of planning, learning and recording. The compliance reviews are not about punishing poor compliance but on helping veterinarians ensure they are doing good quality, relevant CPD. When that’s not happening, it is generally clear to us on review, even without looking at points, and we don’t expect that to change.

How will vets know if they’ve done enough CPD?

The vast majority of veterinarians do more than the currently required minimum amounts of CPD. We don’t expect that the amount of CPD done will change significantly with these changes and most veterinarians will continue to do plenty of CPD. We believe that focussing on the quantity of CPD is less helpful than focussing on the quality of CPD and the process of planning and recording, which will help get more benefit from the CPD that is done.

However, we will provide some general guidelines to help veterinarians and employers identify roughly how much CPD they should aim to do each year. We may refer to this when doing compliance checks, as a guide.

What about NZVA’s MyCPD?

We are working with NZVA to make sure that their CPD platform and the CPD requirements work together.

Proposed changes for new vets

We propose an enhanced version of CPD for new graduates. This would add to the new general CPD scheme set out above by expecting new graduates to:

- Conduct a planning session with a senior colleague (mentor) when they start work. This would normally incorporate the CPD planning process (step 1 above) and is likely to be more detailed and specific than more experienced vets’ plans.

- Meet regularly with their mentor to review progress against the plan and check on their wellbeing. This should be at least monthly for the first 3 months and bimonthly after that until the end of their first year (or more frequently if required for the individual).

We will allow flexibility in who can be a mentor in different situations. A mentor could be an employer or supervisor at work or it could be someone independent. We will ensure that there is a system in place to allow new graduates to request, and be assigned to, an independent mentor. Multiple mentors with different skillsets would also be possible.

New graduates will need good mentors. Normally, we would expect the employer to provide this, however we will also ensure that independent mentors are available. We will ensure that high-quality training is available for those wanting to mentor new graduates and we will help where new graduates report concerns about mentoring to us. Generally, we would try to help the person be a better mentor although in extreme cases we might restrict a person’s ability to mentor new graduates. We will also develop guidance to help with the planning process set out above.

When will all this happen?

If we go ahead with the proposed changes, we plan to run a pilot year from 1 January to 31 December 2021. This will involve all veterinarians being asked to give the new programme a go and we won’t be strictly enforcing it while everyone gets used to it. We may need to make changes based on how the pilot year goes. Veterinarians would only be asked to comply with the new programme (and not the current CPD requirements) during the pilot year. All going well, we would then continue the programme from 2022 on.

If feedback from this consultation leads us to rethink our proposal, we will need more time and it is likely any changes will not take place until 2022 (with the current system continuing in the meantime).

Measuring the effectiveness of our work

We need to be able to tell whether any changes we make are effective and helpful. To do this, we are asking veterinarians to help us by filling out a quick survey now (see below) and we’ll gather more data once any changes have been implemented.

Give us your feedback

Feedback has closed.